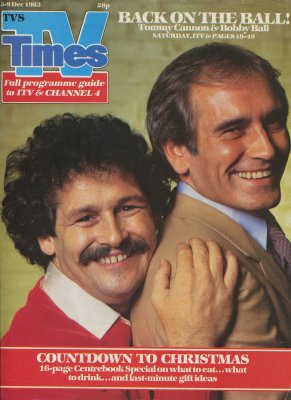

Tommy and Bobby

We don’t know why we’re so successful

By Linda Hawkins

Bobby Ball and dancing around the dressing room, a brilliant idea fizzing and popping in his head, fairly bursting to get out. “There was this fella last night, eight foot tall, Tommy! He was, he must have been eight feet! Well, I thought we could get one of his suits and…”

Bobby Ball and dancing around the dressing room, a brilliant idea fizzing and popping in his head, fairly bursting to get out. “There was this fella last night, eight foot tall, Tommy! He was, he must have been eight feet! Well, I thought we could get one of his suits and…”

Tommy Cannon, seated in front of the dressing table, sips his tea and listens gravely. “Yes, well…keep it short. It’s got to be short”

He puts down his cup and slowly considers the scenario from every angle. “Yes, it might work. We’ll give it a try. But it’s got to be short. It’s got to be fast.” And there, in the dressing room, just a few minutes before curtain up, a new joke is hammered into shape for a future act.

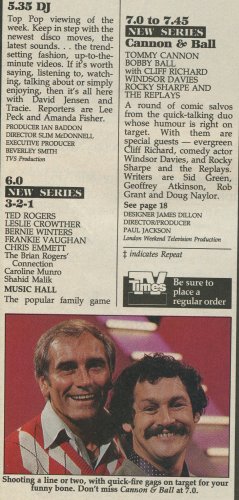

Cannon and Ball, recently voted the Variety Club Showbusiness Personalities of the Year, are probably Britain’s most successful double act since Morecambe and Wise. This spring they set a record for one-night variety acts by cramming 134 shows in 45 theatres into a 13 week tour. As we talk they’ve just completed a similar autumn tour, and are about to start work on their new TV series, starting on ITV this week. So, if they feel a little fatigued, no-one can blame them.

Bobby Ball, his moment of inspiration past, collapses quietly on to a sofa, all vitality temporarily drained.

Yes, we’ve been successful these past few years, but we haven’t had time to take it all in. We’ve never been able to sit down and think about it. Things have been going too fast for us.” But even if there had been time, they are not given to introspection. At heart, they remain plain Lancashire lads, more at home on the factory floor than in some of the posh hotels they find themselves in today, where the food is hidden under sauces that don’t come out of bottles, and a flashing smile isn’t always a sign that you’ve found a friend.

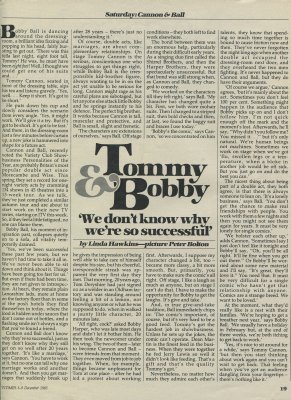

Cannon and Ball don’t know why they’re so successful, just as they don’t know why they still get on so well after 20 years together. “It’s like a marriage,” says Cannon. “You have to work at it, but no-one can tell you why one marriage works and another doesnt. And then you get marriages that suddenly break up after 28 years – there’s just no understanding it”

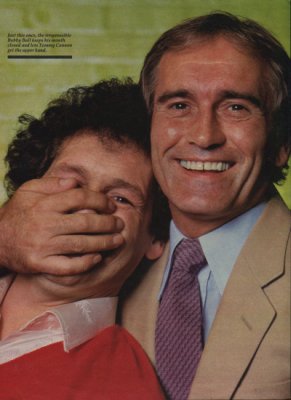

Of course, double acts, like marriages, are about complementary relationships. On stage Tommy Cannon is the serious, conscientious one who struggles to get things right, while Bobby Ball is the irresponsible kid-brother figure, always wanting to be in on the act yet unable to be serious for long. Cannon might rage as his careful plans are sabotaged, but let anyone else attack little Bobby and he springs instantly to his defence. The perfect big brother. It works because Cannon is tall, muscular and protective, and Ball is small, slight and frenetic.

“The characters are extensions of ourselves,” says Ball. Off stage he gives the impression of being well able to take care of himself despite his size, but his cheerful, irresponsible streak was apparent the very first day they met. That morning, 20 years ago, Tom Derbyshire had just signed on as a welder in an Oldham factory and was standing around feeling a bit of a lemon, not knowing anyone or what he was supposed to do, when in walked a jaunty little character, 20 minutes late.

“All right, cock?” asked bobby Harper, who was late most days and didn’t let it bother him. He then took the newcomer under his wing. The two of them – later to become Cannon and Ball – were friends from that moment. They even moved from job to job together. When, for example, things became unpleasant for Tommy at one place – after he had led a protest about working conditions – they both left to find work elsewhere.

The bond between them was an enormous help, particularly during their difficult early years. As a singing duo first called the Shirrel Brothers, and then the Harper Brothers, they were specatcularly unsuccessful. But that bond was still strong when, as Cannon and Ball, they changed to comedy.

“We worked on the characters till they felt right,” says Ball. “My character has changed quite a bit. First, we both wore mohair suits. Then I changed to a striped suit, then bold checks and then, at last, we found the baggy suit and braces I use today.”

“Bobby’s the comic,” says Cannon, “so we concentrated on him first. Afterwards I suppose my character changed a bit, too – became more classy, a bit more smooth. But, primarily, you have to make sure the comic’s all right. Off stage, I like a laugh as much as anyone, but on stage I can’t do that. I have to make the opportunity for Bobby to get the laughs. It’s give and take.

And, in true give-and-take tradition, Ball immediately chips in: “The comic’s important, of course, but it’s very hard to be a good feed. Tommy’s got the hardest job in showbusiness. Unless he sets up the jokes, the comic can’t operate. Dean Martin is the finest feed in the business. When they were together he fed Jerry Lewis so well it didn’t look like feeding. That’s a gift and that’s the quality Tommy’s got.”

Nevertheless, no matter how much they admire each others talents they know that spending so much time together is bound to cause friction now and then. They’ve never forgotten the night long ago when another double act occupied the dressing room next door, and they overheard the two men fighting. It’s never happened to Cannon and Ball, but they do have their arguments.

“Of course we argue,” Cannon agrees, “but it’s mainly about the act. Sometimes you don’t feel 100 per cent. Something might happen in the audience that Bobby picks up on and I don’t follow him. I’m not quick enough off the mark and the moment’s lost. Afterwards he’ll say “Why didn’t you follow me? You missed it…” but it’s only natural. We’re human beings not machines. Sometimes we work on stage when we’ve got ‘flu, swollen legs or a temperature, when a bloke in a nother job would be off sick. But you just go on and do the best you can.”

The nicest thing about being part of a double act, they both agree, is that there is always someone to lean on. “It’s a lonely business,” says Ball. “You don’t get the chance to make real friendships with people. You work with them a few nights and then you might not see them again for years. It must be very lonely for single comics. “

“We bolster each other up,” adds Cannon. “Sometimes I say I just don’t feel like it tonight and Bobby’ll say, “Oh, you’ll be all right. It’ll be fine when you get out there.” Or Bobby’ll be worried about some new material and I’ll say, “It’s great, they’ll love it.” You need that. It must be very difficult for a single comic who hasn’t got that relationship with anyone. Comics are a strange breed. We want to be loved.”

At the moment, what they’d really like is a rest with their families. “We’re hoping to get a breather next year,” says Bobby Ball. “We usually have a holiday in February but, at the end of three weeks, we’re both itching to get back to work.”

“Yes, it’s nice to sit around for a while,” says Tommy Cannon, “but then you start thinking about work again and you can’t wait to get back. That feeling when you’ve got an audience dangling from your fingertips – theres nothing like it.”